All payments are processed in NZD and shipped from New Zealand

All payments are processed in GBP and shipped from England

This year our Christmas card is focused on the Kahikatea, an ancient tree species entirely unique to Aotearoa.

There is a chance we could lose these beautiful Jurassic giants as less than 2% of the original kahikatea forest is left on the North Island, and only a part of this remains in an ecologically viable state.

Part of my childhood was spent living on drained farmlands in the Waikato. My parents worked as dairy farmers. In 2015 I began to learn about the dramatic transformation of much of lowland Aotearoa, particularly the Hauraki Plains. This place feels very familiar to me, it is the main route between the Bay of Plenty (where my family now live) and Auckland, my home for the past ten years. When I learned that the Plains had once been a huge wetland area clothed in giant kahikatea trees, I felt a great sense of loss. Many of the kahikatea trees that are left, (much like Kauri) are exhibiting visible signs of stress and dieback. I’ve noticed the change over the past six years. Many of the trees I first photographed have died, their stands looking spindly and frail. There is a chance we could lose this incredible species.

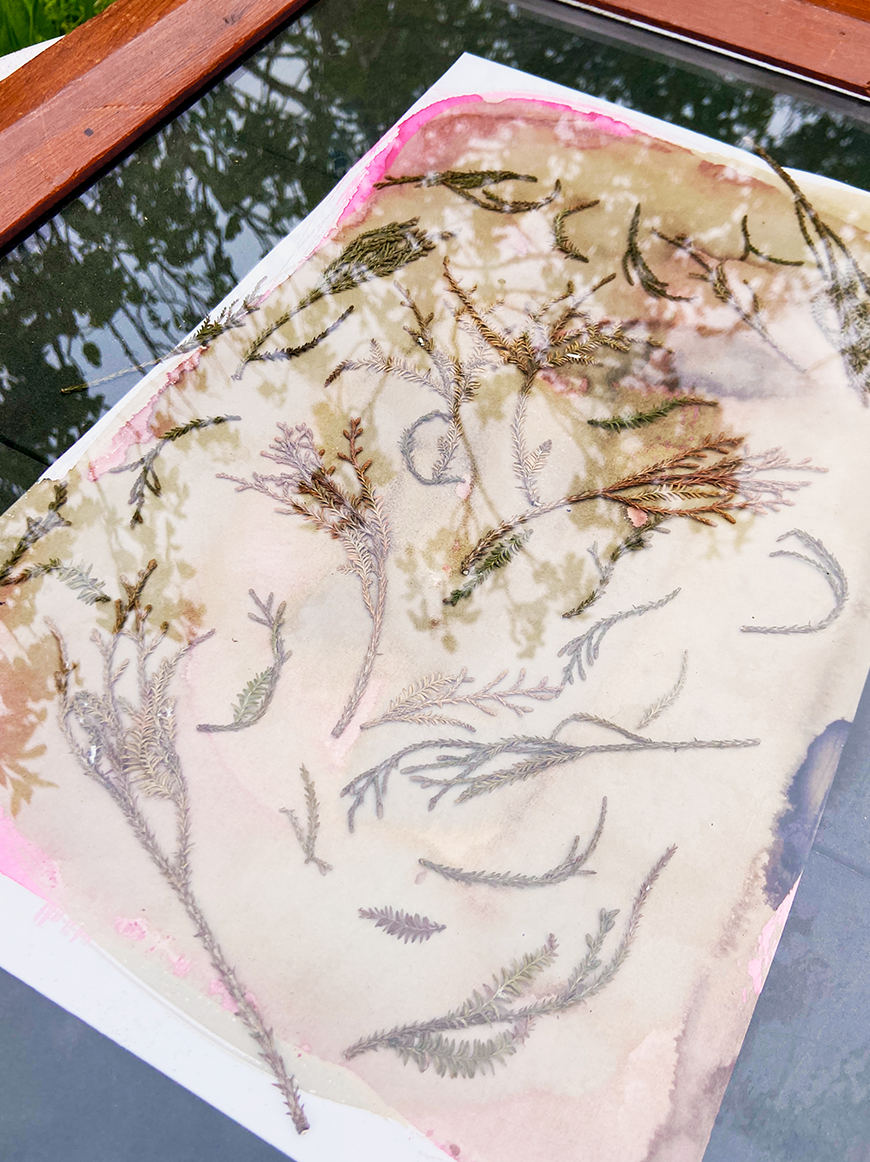

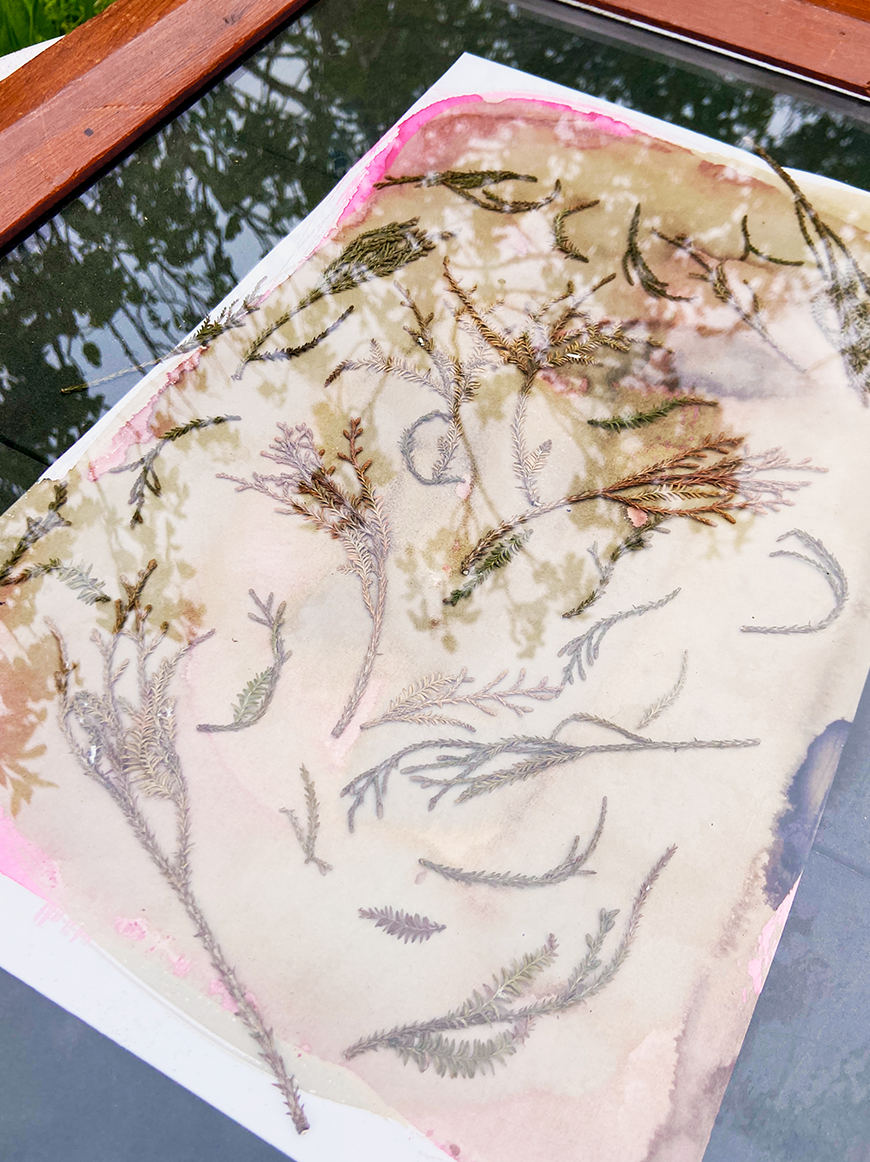

I wanted to use a sustainable method of printmaking for this Christmas card project. The process makes use of common plant dyes and the sun to create a shadowgram.

Kahikatea leaves were sandwiched between coated paper (with plant inks from wisteria, beetroot, and blue pea flower) and glass and left in the sun to fade over a period of days. The resulting image is a pastel-coloured plant-based watercolour and darkened trace of the lovely kahikatea leaves.

My interest in wetlands is layered and multifaceted. They can be unusually exquisite and remarkable places if you give them time. Full of life, beauty, and chaos. Unfortunately, we have drained and filled over 90% of wetlands here in New Zealand so the ones we have left are incredibly precious.

I think most people are aware of how important wetlands are as habitats for our diverse fish and bird species. They act as nurseries, for breeding and feeding. Waters loaded with run-off from land use get filtered through wetlands before entering rivers which travel to the sea. Wetlands are incredible carbon sinks, they are full of plants pulling carbon from the atmosphere. Peatlands (the Hauraki plains are mostly peat soils) store huge amounts of carbon in their accumulated organic matter.

They are also places of ambiguity, sometimes looked down upon with disdain. They are not easy places for people to categorize and define. There is no uniformity, no straight lines, it can be hard to tell where one can walk. In a fantastic book called Ngā Uruora: The Groves of Life, ecologist and Pākehā historian Geoff Park wrote of the Hauraki Plains, “Nothing signals that there is anything special here. Yet a culture’s most precious places are not necessarily visible to the eye. Where English willows now hang in the mud, giant trees once governed the flatness, their dead leaves staining its rivers and streams dark, the air organic with their smells and the conversations of birds.” I think this is an incredibly important sentiment, I didn’t know what those low-lying drained farmlands were before, and I couldn’t decipher how the Hauraki Plains or the lands of my childhood would have functioned prior to drainage. This normalization of new environmental conditions can be seen as a mark of civilization. It can also contribute to an imperialist sense of place and an erasure of history. The health of our ecosystem depends on wetlands. We need to do a better job caring for the ones we have left and, I believe, return many compromised sites back to the watery territory. Returning life force to the Whenua.

2022 has been an incredibly challenging and somewhat exciting year for many of us. I’ve been thinking about ways I can learn to slow down, to do less. The earth would benefit incredibly if we all cooled down our need to be productive.

I’ve decided to spend the next year closer to the places I’ve been making work and more time in the ocean with a move to Whāingaroa/Raglan.

The cover image was taken during a painting with plants class with Geva Downey from Whetū iti workshops.